A Talbot, Kilimanjaro & A Great Story

ONE CHRISTMAS IN THE LIFE OF A TALBOT,

And Some Notes on The Kilimanjaro Expedition

John Whitelock

I n 1955, my brother Keith, who was a keen mountaineer, decided to lead an expedition from Johannesburg to Kilimanjaro. The only vehicles we had were Keith's 1934 Austin 10, his 1926 Sunbeam motorbike, my 1933 Talbot 105 tourer, and my 1934 Talbot 95 saloon. So the 95 was chosen for the trip. None of us had had any experience of other than tarred roads, so after discussions with people I worked with on Daggafontein Mines who had unsuccessfully chased the German General von Lettow in 1917 over that area (when it was German East Africa), extensive preparations were made. Many of these were later found unnecessary and some of them proved almost fatal to the expedition.

The team consisted of Keith, Tony Evans a schoolfriend of Keith's out from the UK after finishing his army service, Ivy, a nurse, and a member of the same mountaineering club as Keith, and John (that's me), the only nonclimber. They took me because I had the car. We proposed leaving in December, returning in January, and this would be the height of the rainy season, so suitable preparations had to be made. I designed steel drums to clip on to the back wheels and Daggafontein Mines blacksmith’s shop made them up. These, together with 200ft of wire rope to wind on these drums, were intended to pull us out of mud and back on to the road using the spinning back wheel. Because of the method of clipping the drums on to the spokes of the wheels, we had to take a left and a right hand one.

The team consisted of Keith, Tony Evans a schoolfriend of Keith's out from the UK after finishing his army service, Ivy, a nurse, and a member of the same mountaineering club as Keith, and John (that's me), the only nonclimber. They took me because I had the car. We proposed leaving in December, returning in January, and this would be the height of the rainy season, so suitable preparations had to be made. I designed steel drums to clip on to the back wheels and Daggafontein Mines blacksmith’s shop made them up. These, together with 200ft of wire rope to wind on these drums, were intended to pull us out of mud and back on to the road using the spinning back wheel. Because of the method of clipping the drums on to the spokes of the wheels, we had to take a left and a right hand one.

They were made from 12-inch diameter steam pipe, flanged on the ends, and weighed about 50 lb each. We also took four steel crowbars 10ft long and four 6ft long to lever us out of awkward spots. In case we were in a situation where there were no trees, we had 6ft lengths of railway line (and railway line weighs 90lb/yard), sharpened to a point at one end and these we intended to drive in to the earth with a 14 lb sledgehammer as an anchor for the wire rope. To test out this winch system, I jacked up a back wheel of the Talbot, fitted one of the drums, and fastening the wire rope to the Austin 10, we pulled the Austin sideways across the garden. We also took rolls of wire mesh for sand mats, and, of course, chains for the tyres. We took an enormous assortment of spares, including a spare front spring.

We had a grinding and drilling head that was driven by a V-belt from a pulley that could be fastened to a back wheel, a blow-lamp and soldering equipment, drills, a hefty vice that could be bolted to a running board, and all my workshop tools, gasket materials, sheets of 1/8", 1/16' mild steel plate and galvanised iron sheet, assorted nuts, bolts and rivets etc. In addition to the party of three boys and one girl, we took four 5-gallon jerry-cans of petrol, four jerry-cans of water, one jerrycan of paraffin, two wooden cases of corned beef, ice axes, and a tent, in addition to the usual camping and mountaineering gear. A month before we set off, I serviced the Talbot as the AA insisted on having an engineering inspection before they would issue a Tryptique to enable us to cross international borders, and this led to the first of our problems. On the Talbot the Wilson preselector gearbox is fed by oil under pressure from the engine lubricating system in addition to having two oil pumps of its own. The oil changing is done by draining the engine and gearbox, then putting 3 gallons of oil in the engine, 1 gallon of which is pumped into the gearbox by the engine oil pump, and a balance pipe back to the sump keeps the gearbox from overflowing. The car passed the AA test with caustic remarks printed on the form concerning the gear lever moving by itself. They just did not understand that this Wilson gearbox self-selects the next gear on the way up, and then preselects third when you are in top (Talbots were ahead of their time). 750 miles later, two days before we were due to leave, the gearbox seized up. I don't know if you have ever seen a Wilson gearbox stripped down, but it is said that Major Wilson went mad designing it and finished up in a mental hospital; this I can understand.

We had a grinding and drilling head that was driven by a V-belt from a pulley that could be fastened to a back wheel, a blow-lamp and soldering equipment, drills, a hefty vice that could be bolted to a running board, and all my workshop tools, gasket materials, sheets of 1/8", 1/16' mild steel plate and galvanised iron sheet, assorted nuts, bolts and rivets etc. In addition to the party of three boys and one girl, we took four 5-gallon jerry-cans of petrol, four jerry-cans of water, one jerrycan of paraffin, two wooden cases of corned beef, ice axes, and a tent, in addition to the usual camping and mountaineering gear. A month before we set off, I serviced the Talbot as the AA insisted on having an engineering inspection before they would issue a Tryptique to enable us to cross international borders, and this led to the first of our problems. On the Talbot the Wilson preselector gearbox is fed by oil under pressure from the engine lubricating system in addition to having two oil pumps of its own. The oil changing is done by draining the engine and gearbox, then putting 3 gallons of oil in the engine, 1 gallon of which is pumped into the gearbox by the engine oil pump, and a balance pipe back to the sump keeps the gearbox from overflowing. The car passed the AA test with caustic remarks printed on the form concerning the gear lever moving by itself. They just did not understand that this Wilson gearbox self-selects the next gear on the way up, and then preselects third when you are in top (Talbots were ahead of their time). 750 miles later, two days before we were due to leave, the gearbox seized up. I don't know if you have ever seen a Wilson gearbox stripped down, but it is said that Major Wilson went mad designing it and finished up in a mental hospital; this I can understand.

What happened was that the gauze filter on the pressure supply from the engine had become blocked with dirt and the gearbox had had no oil. I very carefully, on a large sheet of plywood, stripped the Talbot 95 gearbox and then the one from the 105, which unfortunately was an older design and not the same outside (it was fed by oil pressure through the crankshaft, not by the external pipe, and to change boxes would mean changing crankshafts), and I built one box out of the two. On Talbots the back axle has to be taken apart to remove it, so that the torque tube can be withdrawn in order to get the gearbox off and the job was finished the day before we were due to set off. On the morning we were to leave, we spotted a leak at the water pump gland. Repacking the gland is not an easy job on a Talbot, as the water pump has to be removed. And to do this the radiator has to come off. The radiator is bolted solidly to the engine, and the bonnet bolts on to the radiator. But by 6 o'clock that night we had finished and were loaded up. We set off at 9 o'clock that night and struggled to maintain 35 mph for the 10 hours it took us to the Rhodesian border at Beitbridge, driving in 2-hour shifts. Between Beitbridge and Fort Victoria we had our first blow out, on a rear wheel, and battled for two hours to get the wheel off.

What happened was that the gauze filter on the pressure supply from the engine had become blocked with dirt and the gearbox had had no oil. I very carefully, on a large sheet of plywood, stripped the Talbot 95 gearbox and then the one from the 105, which unfortunately was an older design and not the same outside (it was fed by oil pressure through the crankshaft, not by the external pipe, and to change boxes would mean changing crankshafts), and I built one box out of the two. On Talbots the back axle has to be taken apart to remove it, so that the torque tube can be withdrawn in order to get the gearbox off and the job was finished the day before we were due to set off. On the morning we were to leave, we spotted a leak at the water pump gland. Repacking the gland is not an easy job on a Talbot, as the water pump has to be removed. And to do this the radiator has to come off. The radiator is bolted solidly to the engine, and the bonnet bolts on to the radiator. But by 6 o'clock that night we had finished and were loaded up. We set off at 9 o'clock that night and struggled to maintain 35 mph for the 10 hours it took us to the Rhodesian border at Beitbridge, driving in 2-hour shifts. Between Beitbridge and Fort Victoria we had our first blow out, on a rear wheel, and battled for two hours to get the wheel off.

The splines on the wheel hub had twisted slightly and it took all our wheel-pullers and great clouts with the 14 lb hammer before the wheel came off. On our way again, we stopped for the night near Fort Victoria, having done about 600 miles in 20 hours. We camped at the roadside, and on checking the car the next morning, I discovered that the weight was so great that the cantilever rear springs were so flat that they were being supported by the brake rods, holding the brakes on. So, I slackened the rear brakes right off, and we drove on from there using front brakes only. We could then cruise at 45 to 50 mph on the strip roads and the petrol consumption improved considerably. That day we reached Umvuma, about 100 miles further on, and, proceeding gently down the slight slope of the main street, saw a sign saying 'Falcon Inn'. I pressed the brake pedal hard which put the front brakes full on, selected reverse on the Wilson box, and the splines stripped on the rear hub as we reversed (Talbots, like all good sports cars, had splined wheel hubs). Using all the facilities of Strangeways Garage just across the road, and half the beer in the Falcon, it took 6 hours to get the wheel off. Whilst sitting in the Falcon discussing the practicalities of welding the wheel on, a Caltex salesman came in and offered to take me to Salisbury to look for a splined hub. So off I went, leaving the rest of the party camped outside the Inn, on the pavement. They were not popular when they hung their washing on a line strung between the veranda posts outside; the landlord considered it lowered the tone. In Salisbury I was introduced to two vintage club members at Pioneer Motors, a second-hand car sales place that was an excuse for vintage enthusiasts to gather at lunchtimes and after work before going to the Chalet across the road for draught beer.

The splines on the wheel hub had twisted slightly and it took all our wheel-pullers and great clouts with the 14 lb hammer before the wheel came off. On our way again, we stopped for the night near Fort Victoria, having done about 600 miles in 20 hours. We camped at the roadside, and on checking the car the next morning, I discovered that the weight was so great that the cantilever rear springs were so flat that they were being supported by the brake rods, holding the brakes on. So, I slackened the rear brakes right off, and we drove on from there using front brakes only. We could then cruise at 45 to 50 mph on the strip roads and the petrol consumption improved considerably. That day we reached Umvuma, about 100 miles further on, and, proceeding gently down the slight slope of the main street, saw a sign saying 'Falcon Inn'. I pressed the brake pedal hard which put the front brakes full on, selected reverse on the Wilson box, and the splines stripped on the rear hub as we reversed (Talbots, like all good sports cars, had splined wheel hubs). Using all the facilities of Strangeways Garage just across the road, and half the beer in the Falcon, it took 6 hours to get the wheel off. Whilst sitting in the Falcon discussing the practicalities of welding the wheel on, a Caltex salesman came in and offered to take me to Salisbury to look for a splined hub. So off I went, leaving the rest of the party camped outside the Inn, on the pavement. They were not popular when they hung their washing on a line strung between the veranda posts outside; the landlord considered it lowered the tone. In Salisbury I was introduced to two vintage club members at Pioneer Motors, a second-hand car sales place that was an excuse for vintage enthusiasts to gather at lunchtimes and after work before going to the Chalet across the road for draught beer.

.png) John Wilson, the proprietor, was rebuilding a MG K3 Magnette with a MG J2 engine and Tony Peacock was tuning a Lancia Lambda, all for some races the following week. A search of Salisbury with Tony Peacock revealed no sign of Talbots, other than one known to be buried under the new railway marshalling yard; and Crossley, Lagonda, M.G. etc. hubs were either too big or too small. I then phoned Johannesburg and persuaded my father to take both rear hubs off the 105 and send them up to Salisbury by air. Three days later I was back in Umvuma with the hubs, fitted the right side one, and we were off to Salisbury. We called on John Wilson and, whilst he wasn't looking, left a pile of valuable scrap metal for him in a corner - including two winch drums, 200 ft of wire rope, a large assortment of crowbars, several jerry-cans of water, sledgehammers, and enough railway line to run to Meikles Hotel. Continuing on our journey, we camped on the north side of Salisbury, and had a trouble-free run for a day to Chirundu on the Zambezi River, the border between Southern and Northern Rhodesia. We just missed Uncle Bob, a famous character in the area who was an itinerant one-man band and sign-writer; all the stores and garages on the way had signs with his signature, 'Uncle Bob'. But we did meet some odd characters at the hotel at Chirundu, including another itinerant, a vet who travelled in his Chevrolet van all over the Rhodesias and Mozambique, and whose wife made ear-rings from the scales of fish they caught on the Mozambique coast, selling them in the pubs to get beer money.

John Wilson, the proprietor, was rebuilding a MG K3 Magnette with a MG J2 engine and Tony Peacock was tuning a Lancia Lambda, all for some races the following week. A search of Salisbury with Tony Peacock revealed no sign of Talbots, other than one known to be buried under the new railway marshalling yard; and Crossley, Lagonda, M.G. etc. hubs were either too big or too small. I then phoned Johannesburg and persuaded my father to take both rear hubs off the 105 and send them up to Salisbury by air. Three days later I was back in Umvuma with the hubs, fitted the right side one, and we were off to Salisbury. We called on John Wilson and, whilst he wasn't looking, left a pile of valuable scrap metal for him in a corner - including two winch drums, 200 ft of wire rope, a large assortment of crowbars, several jerry-cans of water, sledgehammers, and enough railway line to run to Meikles Hotel. Continuing on our journey, we camped on the north side of Salisbury, and had a trouble-free run for a day to Chirundu on the Zambezi River, the border between Southern and Northern Rhodesia. We just missed Uncle Bob, a famous character in the area who was an itinerant one-man band and sign-writer; all the stores and garages on the way had signs with his signature, 'Uncle Bob'. But we did meet some odd characters at the hotel at Chirundu, including another itinerant, a vet who travelled in his Chevrolet van all over the Rhodesias and Mozambique, and whose wife made ear-rings from the scales of fish they caught on the Mozambique coast, selling them in the pubs to get beer money.

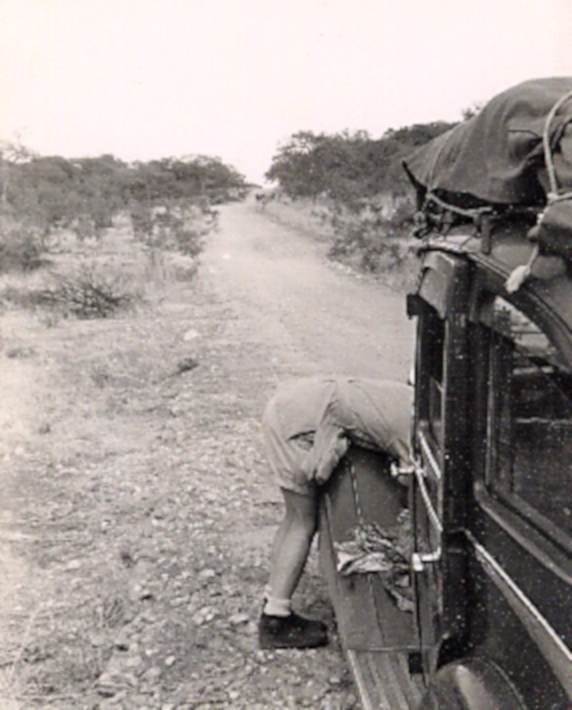

We camped outside on the lawn at the Hotel, as did everyone else (I don't think that the hotel rooms are ever used in that heat) after we were ejected from the bar at about one o'clock in the morning. A policeman in the bar asked us to take his reports and other documents to the Police Station in Lusaka, so we collected these from him the next morning. Oh, and somebody who camped for the night in his car further up the escarpment, with his doors open to keep cool, was taken by a lion that night. On the next day to Lusaka, dropped off the documents at the Police Station, then on to Broken Hill and at Kapiri Mposhi we turned off the strips for the 500 mile stretch of dust and rocks to Tanganyika. The road was bad, full of potholes, and a short way along it the temperature shot up - no water in the radiator. The rigid mounting of the radiator on the engine block combined with a rigid mounting of the engine plus ancient fatigued solder, plagued us for the rest of the trip. On average once a day we had to remove the radiator and re-solder it. At Mkushi River, after drinks at the hotel, we camped in the garden but were chased out of the grounds by the proprietors, so we camped outside their gate. We were glad to have the four spare jerry-cans of petrol and the Talbot's 20-gallon tank, as the petrol stations were out of fuel on this stretch. Next night was at Mpika at the Crested Crane Hotel where we became involved in a darts match with other guests. Claim to fame of this place is that it was an emergency airfield built during the war. We again camped in the garden and nobody objected (it was raining heavily).

We camped outside on the lawn at the Hotel, as did everyone else (I don't think that the hotel rooms are ever used in that heat) after we were ejected from the bar at about one o'clock in the morning. A policeman in the bar asked us to take his reports and other documents to the Police Station in Lusaka, so we collected these from him the next morning. Oh, and somebody who camped for the night in his car further up the escarpment, with his doors open to keep cool, was taken by a lion that night. On the next day to Lusaka, dropped off the documents at the Police Station, then on to Broken Hill and at Kapiri Mposhi we turned off the strips for the 500 mile stretch of dust and rocks to Tanganyika. The road was bad, full of potholes, and a short way along it the temperature shot up - no water in the radiator. The rigid mounting of the radiator on the engine block combined with a rigid mounting of the engine plus ancient fatigued solder, plagued us for the rest of the trip. On average once a day we had to remove the radiator and re-solder it. At Mkushi River, after drinks at the hotel, we camped in the garden but were chased out of the grounds by the proprietors, so we camped outside their gate. We were glad to have the four spare jerry-cans of petrol and the Talbot's 20-gallon tank, as the petrol stations were out of fuel on this stretch. Next night was at Mpika at the Crested Crane Hotel where we became involved in a darts match with other guests. Claim to fame of this place is that it was an emergency airfield built during the war. We again camped in the garden and nobody objected (it was raining heavily).

Next day, on to the Northern Rhodesian/Tanganyika border at Tunduma. We cleared Customs, but Immigration had to be done at the Police Station in Mbeya 70 miles away. So we had a drink or five in the tiny bar of the hotel at Tunduma whilst the rain poured down; it was our first taste of East African beer. The landlord kept warning us, ‘Beware of the I.P.A.’, which came in quart bottles, but we enjoyed it and would rather say, ‘beware of the Baby Tusker’ (similar to Carlsberg Elephant). Half way to Mbeya we camped and, next morning, drove into Mbeya at about 10 o'clock in the morning. In Mbeya as we went down a side road, a slight gradient down, we saw a sign 'Queen's Hotel', jammed on brakes, into reverse, stripped splines on other side. We knew from experience what to do to get the wheel off, and of course I had the spare hub for that side, so we adjourned to the bar. At 2 o'clock we went into the dining room for lunch and found the place deserted, chef gone to sleep, also the manager. We discovered after some argument that East African time is an hour ahead of Southern African time. Whilst working on the car we met an Anglo-American geologist, Don Mustard, whom Keith and I had known when he was based on Springs Mines in South Africa when Keith and I worked there, and his girlfriend, who was teaching at the European boarding school in Mbeya. As we were not going to finish the job before dark, we decided to stay at the hotel. One of us booked a single room and after a good party the other five of us climbed in the window and slept on the floor. But the landlord had his revenge, he charged for the one person and six baths extra (and we hadn't had a bath!)

Next day, on to the Northern Rhodesian/Tanganyika border at Tunduma. We cleared Customs, but Immigration had to be done at the Police Station in Mbeya 70 miles away. So we had a drink or five in the tiny bar of the hotel at Tunduma whilst the rain poured down; it was our first taste of East African beer. The landlord kept warning us, ‘Beware of the I.P.A.’, which came in quart bottles, but we enjoyed it and would rather say, ‘beware of the Baby Tusker’ (similar to Carlsberg Elephant). Half way to Mbeya we camped and, next morning, drove into Mbeya at about 10 o'clock in the morning. In Mbeya as we went down a side road, a slight gradient down, we saw a sign 'Queen's Hotel', jammed on brakes, into reverse, stripped splines on other side. We knew from experience what to do to get the wheel off, and of course I had the spare hub for that side, so we adjourned to the bar. At 2 o'clock we went into the dining room for lunch and found the place deserted, chef gone to sleep, also the manager. We discovered after some argument that East African time is an hour ahead of Southern African time. Whilst working on the car we met an Anglo-American geologist, Don Mustard, whom Keith and I had known when he was based on Springs Mines in South Africa when Keith and I worked there, and his girlfriend, who was teaching at the European boarding school in Mbeya. As we were not going to finish the job before dark, we decided to stay at the hotel. One of us booked a single room and after a good party the other five of us climbed in the window and slept on the floor. But the landlord had his revenge, he charged for the one person and six baths extra (and we hadn't had a bath!)

The next day we detoured over the hills to Chunya, a ghost town on the Lupa goldfields, which at one time had a European population of 3,000 and now only 2 remained. The postmistress, who had refused to leave when everyone else went, regaled us with stories about the Wild West style living in the old days - the girls used to hold auctions on the bar at closing time and hardly a car in town did not have its hood riddled with shotgun pellets. The Mining Commissioner for the area, at whose house we stayed, lived in a long street of big houses and, as all the other ones were empty, if he wanted a change of view he just moved house. Back at Mbeya the next day, we camped at the boarding school that night, then the following day moved off along the Great North Road to Iringa, 250 miles away. The rains were getting heavy now and the mud was thick. When it was dry the sand was six inches deep, so the going was hard. We never saw any vehicles on these roads other than 6x4 or 6x6 lorries, and the ubiquitous Land Rovers. In towns the most common cars were Peugeot 203s (I drove up to Malawi from Johannesburg in a 203 in 1963, and eventually bought another one in Malawi; they were great cars) and Fiat 1100s. Some of the drifts were raging torrents and at one of them, after taking a run at it and ploughing past a couple of buses which were stuck in the river, we hit a pothole in the middle with a tremendous jar that shook half the solder off the radiator. So, on reaching the opposite bank, we camped and under a tarpaulin spent two days soldering it back up. On to Iringa with the tyres now giving more trouble. The sidewalls of the old 650 x 18 tyres were collapsing. Fortunately, in Iringa we contacted a vet, Guy Yeoman, who had climbed in the Himalayas and he put us up, fed us, and encouraged us to drink his I.P.A. whilst we waited for a new tyre to come from Dar es Salaam by air. The only 18" tyre available was a 550, not a 650, so it had to go on a front wheel, to keep the rear wheels the same size. Another 250 miles to Dodoma, where we stayed with Duncan, a Government geologist, and John worked all night on the radiator and also on a broken exhaust pipe.

The next day we detoured over the hills to Chunya, a ghost town on the Lupa goldfields, which at one time had a European population of 3,000 and now only 2 remained. The postmistress, who had refused to leave when everyone else went, regaled us with stories about the Wild West style living in the old days - the girls used to hold auctions on the bar at closing time and hardly a car in town did not have its hood riddled with shotgun pellets. The Mining Commissioner for the area, at whose house we stayed, lived in a long street of big houses and, as all the other ones were empty, if he wanted a change of view he just moved house. Back at Mbeya the next day, we camped at the boarding school that night, then the following day moved off along the Great North Road to Iringa, 250 miles away. The rains were getting heavy now and the mud was thick. When it was dry the sand was six inches deep, so the going was hard. We never saw any vehicles on these roads other than 6x4 or 6x6 lorries, and the ubiquitous Land Rovers. In towns the most common cars were Peugeot 203s (I drove up to Malawi from Johannesburg in a 203 in 1963, and eventually bought another one in Malawi; they were great cars) and Fiat 1100s. Some of the drifts were raging torrents and at one of them, after taking a run at it and ploughing past a couple of buses which were stuck in the river, we hit a pothole in the middle with a tremendous jar that shook half the solder off the radiator. So, on reaching the opposite bank, we camped and under a tarpaulin spent two days soldering it back up. On to Iringa with the tyres now giving more trouble. The sidewalls of the old 650 x 18 tyres were collapsing. Fortunately, in Iringa we contacted a vet, Guy Yeoman, who had climbed in the Himalayas and he put us up, fed us, and encouraged us to drink his I.P.A. whilst we waited for a new tyre to come from Dar es Salaam by air. The only 18" tyre available was a 550, not a 650, so it had to go on a front wheel, to keep the rear wheels the same size. Another 250 miles to Dodoma, where we stayed with Duncan, a Government geologist, and John worked all night on the radiator and also on a broken exhaust pipe.

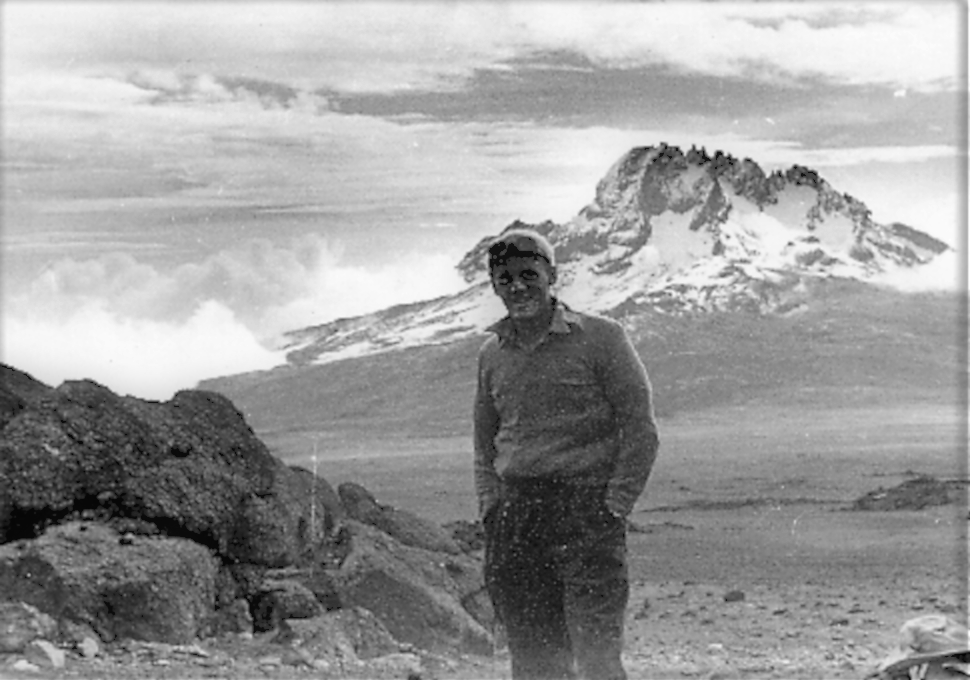

The next day we drove on over Pienaar's Heights, a famous area in WW1, to Arusha, and then a tarred road down to Moshi, the town nearest to Kilimanjaro. We arrived on Christmas Day, so celebrated suitably at the Kibo Hotel run by an old German woman. Afterwards we spent 3 weeks climbing on Kibo and Mwenzi peaks, and a brief description by a non-climber (myself) amongst three climbers follows: Mount Kilimanjaro is the highest mountain in Africa at 19,000 feet. It consists of two peaks separated by a saddle at about 15,000 feet above sea level. Kibo is the higher and is a gradual slope up to a crater on the top. The hardest part about climbing it was (a) the 70 lb packs Keith insisted on each one taking, and (b) the altitude sickness that set in at about 15,000 feet. In the dry season the next problem would be the scree that covers the ground so that three steps forward lead to two steps sliding back, but due to Keith's insistence on going in the rainy season, this scree was covered with snow, making it a bit easier. There are some rest huts on the way up and we made use of these.

The next day we drove on over Pienaar's Heights, a famous area in WW1, to Arusha, and then a tarred road down to Moshi, the town nearest to Kilimanjaro. We arrived on Christmas Day, so celebrated suitably at the Kibo Hotel run by an old German woman. Afterwards we spent 3 weeks climbing on Kibo and Mwenzi peaks, and a brief description by a non-climber (myself) amongst three climbers follows: Mount Kilimanjaro is the highest mountain in Africa at 19,000 feet. It consists of two peaks separated by a saddle at about 15,000 feet above sea level. Kibo is the higher and is a gradual slope up to a crater on the top. The hardest part about climbing it was (a) the 70 lb packs Keith insisted on each one taking, and (b) the altitude sickness that set in at about 15,000 feet. In the dry season the next problem would be the scree that covers the ground so that three steps forward lead to two steps sliding back, but due to Keith's insistence on going in the rainy season, this scree was covered with snow, making it a bit easier. There are some rest huts on the way up and we made use of these.

At the top there are no huts, so we camped in the crater amongst the ice, with a large iceberg next to us. Very few photos of our climb are available because the official photographer, Tony, was affected by mountain sickness and for several days forgot to take the lens cover off. It was so cold in the tent in the crater that we were awake all night and tried to make tea by filling the kettle with snow and melting it, but it takes a lot of snow to fill a kettle, and when we did manage to get a full kettle to boil, the Primus stove melted the ice underneath it and it tipped over spilling its contents. We were physically sick all night and, because it was too cold to go outside, we had to be sick into our boots. It took until 11 o'clock the next day in broad sunshine for it to melt so that we could put our boots on. We did manage to make some tea that morning, just in time to offer it to a party of mountaineers who had just come over the rim of the crater. They were a bit surprised. We then descended to the saddle and crossed to the other peak, Mwenzi, which is a proper mountain. It took us two days to cross the saddle to the hut at the base of Mwenzi and, as we approached, we saw another party of four mountaineers leaving for their climb. On reading the log book, we saw that the party was led by Alistair Cram, whom I had climbed with from Aviemore Youth Hostel in Scotland in 1951, before Keith and I left England. Alistair was a bit eccentric and whilst we were climbing one of the Munros (hills over 3,000ft) in Scotland he put a small stone on a rock, walked on for about 20 yards, produced a gun from his pack with a barrel about 18" long, and proceeded to take pot-shots at the stone. At that time, he was a magistrate in Kenya (Mau Mau time) on home leave, and he said this was a very necessary drill for Africa.

At the top there are no huts, so we camped in the crater amongst the ice, with a large iceberg next to us. Very few photos of our climb are available because the official photographer, Tony, was affected by mountain sickness and for several days forgot to take the lens cover off. It was so cold in the tent in the crater that we were awake all night and tried to make tea by filling the kettle with snow and melting it, but it takes a lot of snow to fill a kettle, and when we did manage to get a full kettle to boil, the Primus stove melted the ice underneath it and it tipped over spilling its contents. We were physically sick all night and, because it was too cold to go outside, we had to be sick into our boots. It took until 11 o'clock the next day in broad sunshine for it to melt so that we could put our boots on. We did manage to make some tea that morning, just in time to offer it to a party of mountaineers who had just come over the rim of the crater. They were a bit surprised. We then descended to the saddle and crossed to the other peak, Mwenzi, which is a proper mountain. It took us two days to cross the saddle to the hut at the base of Mwenzi and, as we approached, we saw another party of four mountaineers leaving for their climb. On reading the log book, we saw that the party was led by Alistair Cram, whom I had climbed with from Aviemore Youth Hostel in Scotland in 1951, before Keith and I left England. Alistair was a bit eccentric and whilst we were climbing one of the Munros (hills over 3,000ft) in Scotland he put a small stone on a rock, walked on for about 20 yards, produced a gun from his pack with a barrel about 18" long, and proceeded to take pot-shots at the stone. At that time, he was a magistrate in Kenya (Mau Mau time) on home leave, and he said this was a very necessary drill for Africa.

.png)

On a previous home leave, he had successfully found some climbers lost in the Cairngorms, but they had died in the cold (there is a book written about this). He eventually came to Malawi as Puisne Judge, but I never met up with him there. The climb up Mwenzi was steep, involving two days of cutting steps up a frozen waterfall, as well as struggling up a steep snowfield and in all we spent a week at that hut going out on different routes each day. The return trip took four weeks. The heaviest rains for many years had set in and the roads between the towns were closed to all traffic except Police, East African Railways and Harbours Road Services lorries. To get through we would coast up to the barriers, then everyone except the driver leapt out, dismantled the barrier and we were through before the watchman, who was sheltering from the rain in his hut, saw what was happening. At Moshi we had bought another 550 x 18 tyre, but after Arusha, the trouble really started. We detoured to Ngorongoro Crater of Serengeti National Park, had a major electrical breakdown at Mto Wa Mbu (River of Mosquitos) where we were attacked in our camp by enormous land crabs. At this stage we were averaging 120 miles, 7 punctures and one radiator rebuild per day.

The rear hub splines were standing up, but the internal ones inside the back wheels gave up, so those wheels had to go on the front. With no splines on the front wheels, putting on the brakes, which were only connected to the front, would spin the RudgeWhitworth centre-lock nut off, and the wheel would go bounding down the road whilst we ground a flat on the brake drum fins. Sometimes it took an hour to find the nut afterwards, so the brakes were only to be used in cases of dire emergency, otherwise we stopped by selecting reverse gear. Because of this spline problem, and having two different size tyres, and we always had to have wheels on the back that were the same size and had good splines - this meant that sometimes a puncture meant changing two tyres to get it right. At every town and village, we stocked up with tyre repair patches, solder, flex, and paraffin for the blowlamp, but at Iringa the radiator finally fell irreparably to pieces. We limped to Guy Yeoman's house, moved into the guest cottage and sent a telegram to Johannesburg asking my father to take the radiator off the 105 Talbot and send it up to us. This arrived two weeks later by which time we had solved the problem of being only able to engage three gears instead of four (one at a time of course) then two, and just before Iringa, bottom gear only. The rear engine mounting had broken. The batteries had also given up (two 12v ones because the Talbot needs 24v for the starter motor), so starting was by cranking or pushing, and all in all we were struggling. The 105 Talbot radiator was about 3 inches lower than the 95 one, so the bonnet had to be modified before we set off. After this, we had no more radiator troubles, but tyre problems persisted and the rain was still pouring down, and at last we got stuck in the mud. I made the mistake of going off the road when faced with an ugly stretch of mud and water and the mud was even deeper there. After a couple of hours struggling to dig the car out (we had brought sets of ex-W.D. entrenching tools with us for such eventualities), we decided to put the chains on and the car just sailed out. From then on, faced with mud, we put the chains on and never got stuck - it was very impressive. We had our only accident on this section, going down a steep hill we were running in the ruts made by lorries and found that there were only three ruts, the middle one being common to both directions. And we met a lorry, bogged down halfway up the hill, with half its wheels in one of our ruts. Brakes on, reverse gear (the wheels don't come off if they are sliding), no difference; turn the steering wheel, ruts too deep so we just continued to slide down the hill until we hit. After digging a way out of the ruts, and pulling the mudguard off the wheel, we carried on to the Northern Rhodesian border where we found the Immigration people very awkward. They thought that the 20 Pounds Sterling we had between us was insufficient to get us to Beitbridge and wouldn't let us in. They eventually proposed that if we telegraphed Johannesburg for money, on production of the money order we could send it back and could go through. We argued that we had sufficient petrol and food to take us through, and besides, we could not afford any delays. I had taken my allowance of 4 weeks leave, with an additional 3 weeks unpaid extension. and I was already 3 weeks overdue on that! After a couple of hours arguing it was 6 p.m. and closing time, and the officer's wife was outside sounding the hooter of the Land Rover because they were going to the cinema 70 miles away in Mbeya, so, very grudgingly, he let us through. After we hit the strip road at Kapiri Mposhi., the trip was uneventful, the old car just purred along. We even enjoyed a couple of beers at the Falcon in Umvuma (the landlord was away). The Talbot eventually recovered, but I later had to import bolt-on wheels and associated hubs for the 105 as well as the 95, because the dreaded stripped spline disease had spread to the other car when wheels were inadvertently changed. When Talbots were new, bolt-on wheels were optional extras, as was the crash gearbox, which I also imported from the man in London who kept old Talbot spares as I never managed to repair the seized Wilson box parts. Lots of lessons were learnt from this trip, not only on how to solder radiators and repair punctures, but also that splined Rudge-Whitworth wheels don't like bush roads, travel as light as possible, fit new tyres and a new radiator before setting off. I did this same route, but even further North, up to Mount Kenya, three years later and went in a Fiat 500 (the air cooled one, so no radiator problems, but plenty of others!)

The rear hub splines were standing up, but the internal ones inside the back wheels gave up, so those wheels had to go on the front. With no splines on the front wheels, putting on the brakes, which were only connected to the front, would spin the RudgeWhitworth centre-lock nut off, and the wheel would go bounding down the road whilst we ground a flat on the brake drum fins. Sometimes it took an hour to find the nut afterwards, so the brakes were only to be used in cases of dire emergency, otherwise we stopped by selecting reverse gear. Because of this spline problem, and having two different size tyres, and we always had to have wheels on the back that were the same size and had good splines - this meant that sometimes a puncture meant changing two tyres to get it right. At every town and village, we stocked up with tyre repair patches, solder, flex, and paraffin for the blowlamp, but at Iringa the radiator finally fell irreparably to pieces. We limped to Guy Yeoman's house, moved into the guest cottage and sent a telegram to Johannesburg asking my father to take the radiator off the 105 Talbot and send it up to us. This arrived two weeks later by which time we had solved the problem of being only able to engage three gears instead of four (one at a time of course) then two, and just before Iringa, bottom gear only. The rear engine mounting had broken. The batteries had also given up (two 12v ones because the Talbot needs 24v for the starter motor), so starting was by cranking or pushing, and all in all we were struggling. The 105 Talbot radiator was about 3 inches lower than the 95 one, so the bonnet had to be modified before we set off. After this, we had no more radiator troubles, but tyre problems persisted and the rain was still pouring down, and at last we got stuck in the mud. I made the mistake of going off the road when faced with an ugly stretch of mud and water and the mud was even deeper there. After a couple of hours struggling to dig the car out (we had brought sets of ex-W.D. entrenching tools with us for such eventualities), we decided to put the chains on and the car just sailed out. From then on, faced with mud, we put the chains on and never got stuck - it was very impressive. We had our only accident on this section, going down a steep hill we were running in the ruts made by lorries and found that there were only three ruts, the middle one being common to both directions. And we met a lorry, bogged down halfway up the hill, with half its wheels in one of our ruts. Brakes on, reverse gear (the wheels don't come off if they are sliding), no difference; turn the steering wheel, ruts too deep so we just continued to slide down the hill until we hit. After digging a way out of the ruts, and pulling the mudguard off the wheel, we carried on to the Northern Rhodesian border where we found the Immigration people very awkward. They thought that the 20 Pounds Sterling we had between us was insufficient to get us to Beitbridge and wouldn't let us in. They eventually proposed that if we telegraphed Johannesburg for money, on production of the money order we could send it back and could go through. We argued that we had sufficient petrol and food to take us through, and besides, we could not afford any delays. I had taken my allowance of 4 weeks leave, with an additional 3 weeks unpaid extension. and I was already 3 weeks overdue on that! After a couple of hours arguing it was 6 p.m. and closing time, and the officer's wife was outside sounding the hooter of the Land Rover because they were going to the cinema 70 miles away in Mbeya, so, very grudgingly, he let us through. After we hit the strip road at Kapiri Mposhi., the trip was uneventful, the old car just purred along. We even enjoyed a couple of beers at the Falcon in Umvuma (the landlord was away). The Talbot eventually recovered, but I later had to import bolt-on wheels and associated hubs for the 105 as well as the 95, because the dreaded stripped spline disease had spread to the other car when wheels were inadvertently changed. When Talbots were new, bolt-on wheels were optional extras, as was the crash gearbox, which I also imported from the man in London who kept old Talbot spares as I never managed to repair the seized Wilson box parts. Lots of lessons were learnt from this trip, not only on how to solder radiators and repair punctures, but also that splined Rudge-Whitworth wheels don't like bush roads, travel as light as possible, fit new tyres and a new radiator before setting off. I did this same route, but even further North, up to Mount Kenya, three years later and went in a Fiat 500 (the air cooled one, so no radiator problems, but plenty of others!)

.png)

.png)

THE TALBOT OWNERS CLUB MAGAZINE

The Talbot Owners Club magazine is published bi-monthly and contains news, updates and informative articles. It is edited by club secretary David Roxburgh.

GO TO DOWNLOADS

TALBOT OWNERS CLUB MEMBERSHIP

The essence of the Club is to ensure that members meet and enjoy themselves; the Club is open and democratic, dialogie is encouraged. It is for people of all ages who like Talbot cars and want to enjoy the company of like-minded people and also to support current Talbot involvement in historic competition.